Abstract

Problematic social media use is detrimental to users’ subjective well-being. Based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), we proposed a short-term abstinence intervention to treat this problem. A mixed method study with 65 participants was conducted to examine the effectiveness of this intervention and to reveal the underlying mechanisms of how the intervention influences participants. While the experimental group (N = 33) took eight 2.5-h breaks from social media over two weeks and had daily dairies, the control group (N = 32) used social media as usual and had daily diaries. The results demonstrated that the intervention has a positive effect on life satisfaction. The effect varied with the time users conducted abstinence (work hours vs. off hours) and the level of social media addiction (heavy users vs. normal users). Qualitative findings from dairies and interviews unveiled associations among users’ behaviors, feelings, and cognitions during and after abstinence. These results extend the understanding of the CBT-based short-term abstinence intervention and suggest opportunities to alleviate problematic social media use.

Introduction

As social media is becoming pervasive in our life, the emerging overuse patterns have caused problems, including poor working performance [1] and many other mental detriments [2, 3]. To date, solutions to problematic social media use are still limited. A few studies on this problem have revealed the benefits of getting away from social media, but they did not answer how to guide healthy usage while still in use. Considering the tight connection between social media and our routine life, completely quitting may be infeasible. Therefore, this study proposes a short-term abstinence intervention based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to deal with this problem and guide rational use. We conducted a mixed method study to examine the effects of this intervention and reveal the underlying cognitive and behavioral mechanisms.

Problematic Social Media Use

Problematic use of social media is a maladaptive behavior [4], which could be identified from symptoms like preoccupation with social media, an inability to control social media use, and continued use despite the negative consequences [5]. Problematic social media use has been found to have many negative effects, such as stress [6], reduced well-being [2, 7, 8], distractions [9], poor performance [10] and many other negative emotions [3].

Nowadays, social media is not only used for leisure purposes, but also commonly used in work environments, which has led to emerging problems of work life conflict [9]. The negative effects of problematic social media use also vary between work and life conditions. For the life aspect, problematic social media use is found to decline users’ life satisfaction [7, 11] and have negative effects on offline relationships (e.g., causing family conflict) [1]. For the work aspect, however, the negative effects of problematic use of social media is mainly focusing on the damage of users’ concentration [1, 12]. It will also influence users’ work performance and work satisfaction [1, 13].

Some researchers defined the problematic use of social media as a new kind of behavioral addiction and revealed its deterioration [1, 14,15,16]. Although the latest version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders still does not recognize it as a disorder, scholars have found that social media addiction (SMA) shares symptoms with other addictions [16,17,18], such as withdraw [19], relapse [12] and time distortion [20, 21]. Problematic social media use has, therefore, been identified as a problem in need of resolution.

In recent studies, fear of missing out (FoMO) is found tightly associated with problematic social media use [22,23,24]. FoMO denotes the desire to keep up with what others are doing and the worry about others’ having rewarding experiences when one is absent [23, 25]. FoMO is associated with a decrease of people’s mental well-being and many other negative emotions like anxiety and depression [26]. Therefore, alleviating FoMO may be a possible way to deal with problematic social media use.

Similar to other types of addictions, the development of problematic social media use can also be explained by the reward-based learning process [27]. If a behavior was marked by humans’ mind as a high-reward behavior, it will be more likely performed again than other low-reward behaviors [28]. This process is widely regarded as a cause of addictive disorders, no matter substance abuse or behavioral addictions [29]. Social media use shows a reward superiority over unpleasant and neutral activities in daily life and displacement of these activities extends the use of social media [30]. Thus, finding activities that can displace the use of social media could also be a good idea to address problematic social media use.

Social Media Abstinence

Some users who have realized the negative effects of social media overuse actively attempted to abstain from it as a way of self-regulation [31]. However, the relapse effect is prominent among these non-users [12]. Even though, these non-use behaviors have been found to have positive effects. For example, people who succeeded in quitting Twitter for Lent reported good experiences like closer offline relationships and better time management [32].

Besides the examples of users’ active non-use behaviors, recent years, researchers have designed several abstinence experiments to explore possible solutions to problematic social media use. Morten Tromholt designed an experiment of one-week break from Facebook, in which participants experienced increased life satisfaction and more positive emotions [33]. However, in another one-week abstinence experiment, Stieger and Lewertz found that abstinence caused decreased positive affect and increased boredom, craving and negative affect, which resulted in significant withdraw and relapse effects [19]. Turel, Cavagnaro and Meshi otherwise looked at users’ perceived stress and found significant decrease of stress in their one-week abstinence experiment [20].

The abovementioned abstinence experiments have attempted to deal with SMA through the abstinence approach and these interventions have a common limitation. As social media are interwoven with many aspects with our daily life, continuous abstinence over one week could bring about inconvenience and negative emotions. Therefore, it may not be a feasible method to deal with SMA in the everyday life [19, 21]. Shorter abstinence periods (like hours’ abstinence in a day) may increase the feasibility, but it may also raise concerns of decreased effectiveness [21]. A recent study found that reducing the duration of daily Facebook use for 20 min could improve users’ well-being [34]. This finding implies that intervention in short time periods may still be effective to treat SMA. Thus, in this study, we proposed a new strategy of short-term abstinence and examined its effectiveness. To improve the feasibility of the intervention and to avoid possible negative effects of completely non-use, this strategy only requires continuous hours’ abstinence from social media for a day.

Maladaptive Cognitions and CBT

Understanding the underlying mechanism of SMA is important to determine ways to address it. Researchers found that SMA is significantly related to low self-esteem, narcissism, and loneliness [35,36,37]. Apart from these personality reasons, another important reason is maladaptive cognitions [38]: cognitive biases developed during the use and which contributes to the pathological use of technology [39]. Previous research asserted that users’ cognitions of social media are highly related to their addictive behaviors [3, 39,40,41]. The cognitive-affective-behavioral paradigm claims that behavior is influenced by emotion, and emotion is determined by cognition [42]. A recent study investigating the key cognitive factors contributing to SMA confirmed this paradigm, revealing that maladaptive cognition is a significant predictor to SMA [3]. Thus, a possibly effective way to treat SMA is reconstructing users’ maladaptive cognitions.

The CBT is one of the most commonly used approaches that focus on changing unhelpful cognitive distortions [43, 44]. Although empirical studies of CBT for SMA is now scarce, it has been proved an effective treatment in the prevention of internet addiction and many other compulsive disorders [1, 14]. The CBT improves mental health by influencing behaviors through reconstructed thoughts and feelings [42, 44]. During a CBT session, the method of taking diaries is sometimes used to help record the behaviors and feelings, allowing individuals to explore their mental processes [45], through which, maladaptive cognitions are identified and the corresponding behaviors are modified.

The previous abstinence studies on SMA mainly focused on participants’ mental reactions to social media non-use. The exact compensatory behaviors and the corresponding cognition changes remain undiscovered [19]. We still lack understanding of why social media abstinence could improve personal well-being. Thus, another aim of this study is to discover the underlying cognitive and behavioral mechanisms of social media abstinence. Drawing on the CBT, we used diaries and interviews to discover users’ behaviors and thoughts during the intervention session. These results are aimed to extend our understanding of the influence of short-term abstinence on users’ thoughts and behaviors, which may enlighten future intervention strategies to SMA.

This Study

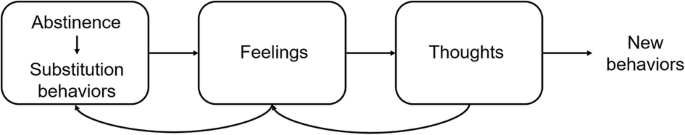

We proposed a short-term abstinence intervention based on CBT to deal with the problematic social media use. Abstinence requires participants to get away from social media. The short-term property differentiated the abstinence in our study from these continuous abstinence over one week in previous research [19, 20, 33]: users only need to take breaks from social media for a few hours within a day, and beyond the abstinence period, they can use social media freely. According to the CBT, in our study, short-term abstinence aims to influence users in such a process (see Fig. 1): abstinence changes users’ routine behaviors of social media use and gets them to take substitution behaviors; these new behaviours produce different feelings; these feelings reconstruct users’ thoughts; then reconstructed thoughts lead to users’ new behaviors. During the intervention session, the thoughts could also influence feelings in an opposite direct and then influence users’ choice of substitution behaviors.

Participants were required to take daily diaries in the two-week intervention session to record their behaviors, feelings, and thoughts. These records were aimed to help users to make self-reflections and were helpful for us to collect data and discover the behavioral and cognitive mechanisms of short-term abstinence. One problem is that, according to the self-monitoring theory, merely tracking one’s using behaviors could improve self-regulation and well-being [46]. Thus, in order to examine the effect of taking abstinence, we included a control group in this study, which only required participants to take daily diaries of social media use but with no abstinence.

Abstinence conducted in different conditions (i.e., work hours or off hours) may have different results. Thus, in this study, when examining the effects of short-term abstinence, we considered the possible difference between work and life. In addition, previous studies also suggested that users with different levels of SMA will react differently to abstinence [21, 33]. Therefore, we also investigated the effect of short-term abstinence under participants’ different levels of SMA (i.e., heavy users vs. normal users).

This study contributes to the literature in two ways. First, we proposed a new intervention strategy to problematic social media use and examined the effects. The new intervention strategy does not require users to quit social media. Second, based on the cognitive process of CBT, we unveiled the underlying mechanisms of abstinence, revealing the associations among the compensatory behaviors and the corresponding feelings and thoughts. This will extend our understanding of why the short-term abstinence could work, and it will enlighten future intervention strategies.

Methodology

Participants

Participants were recruited via invitations posted on SNS (Wechat Moment and Weibo) in China. This study required participants to have more than one year working experience and have never actively moved away from social media. We randomly chose 68 participants from the 448 applicants to join the experiment and assigned them to the experimental group (EG: 36) and the control group (CG: 32). Three participants in the EG quit the experiment after the introduction session. Thus, we finally analysed data collected from 33 EG members and 32 CG members. The demographic information is shown in Table 1. The contrast between two groups shows that no significant differences exist in terms of age, gender, SMA, and maximum acceptable abstinence time (tmax) between the two groups. Informed consent was collected online with the invitation and double checked in the introduction session.

Procedures

To determine the proper abstinence time of this study, we firstly asked a question in the invitation about the maximum time that a user could accept to abstain from social media. The results of the 448 applicants showed that the mean value was 3.2 h (SD = 1.4). Considering a typical CBT intervention session normally lasts around 2 h [47], we finally determined the length of a short-term abstinence in our study to be 2.5 h.

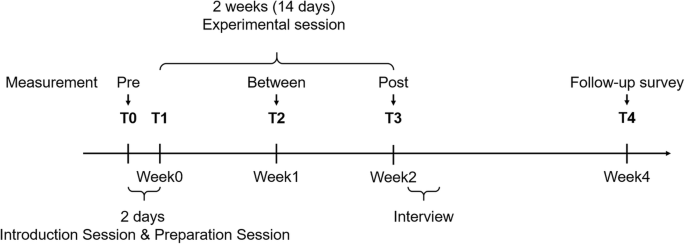

Both groups attended an introduction session before the experiment (T0, see Fig. 2). During the introduction session, participants were guided to use the time management function in their phones to track their daily time use of social media. If the time management function embedded in the operating system did not work, participants were guided to download a new time management application (Moment for iOS and QualityTime for Android).

A two-day preparation session (between T0 and T1) was held after the introduction session, which was intended to make sure all participants could give daily feedback as required. The feedback included a daily dairy and screenshots of the time management function/application showing the exact daily time use on social media. Daily feedbacks were collected via an online system and participants were required to submit them before they went to bed every night. During the preparation session, participants were not required to take abstinence.

The experimental session lasted two weeks (from T1 to T3). Participants in the EG were required to take the short-term abstinence (2.5 h) in four days of each week. Which four days were determined by participants themselves. Half of participants in the EG were assigned to take abstinence during work hours in the first week and then during off hours for a second week. The order of abstinence was reversed for the other half. During abstinence, participants were forbidden to use social media (no use, no touch, and no notifications). We give participants an example list of social media to make them sure which app should be abstained. On the abstinence days, the daily diary focused on difficulties, behaviors, feelings, and thoughts during and after abstinence. On the normal days, it focused on social media usage behaviors, feelings and thoughts. Participants in the CG used social media as usual. They were also required to take daily diaries, which were the same as diaries taken by the participants in the EG on the normal days.

After the experimental session ended, to unveil the underlying mechanisms of how short-term abstinence influenced participants, we conducted a semi-structured interview with each participant in the EG (33 in total: 28 face to face, five by video call). All interview questions were based on the results of diaries and literature review.

Two weeks after the experimental session (T4), each participant in the EG finished a follow-up survey about their behaviors and cognitions after experiment and without abstinence requirement. All participants were compensated with 100–600 Chinese Yuan for their participation in this experiment.

The SMA of each participant was measured in the invitation. The data for life and work satisfaction were collected at three time points: before the introduction session (T0: to avoid possible effect of the introduction and preparation), between the experiment (T2), post experiment and before the interview (T3: to avoid possible effect of the interview). Every day during the experimental session, participants were also required to evaluate their satisfaction to life and work of the day (from 1 to 10) and to give reasons in the diary.

Measures

SMA

The scale used to measure SMA was adapted from Young’s eight-item questionnaire for internet addiction [48] by changing the word “internet” to “social media”. A 5-point Likert scale was used with 1 = not at all, 2 = rarely, 3 = occasionally, 4 = often, and 5 = always. The reliability for the scale was remarkably high with Cronbach’s α larger than 0.89. The original version of Young’s scale was based on yes no questions. As suggested by Young, participants who answered no less than 5 “yes” to the eight questions were regarded as having high addiction. The cut off score of five was proved consistent with former studies about addiction [48]. Following research using Likert scale applied this cut off score by recoding responses of “1,2” to “no” and “3,4,5” to yes [49]. In our study, to contrast possible difference between participants with various SMA, we also used the suggested cut off score to divide the participants into two groups when analysing the data. MEG_highSMA = 6.67 (SDEG_highSMA = 1.15, N = 18), MEG_lowSMA = 2.00 (SDEG_lowSMA = 1.21, N = 15), MCG_highSMA = 6.69 (SDCG_highSMA = 1.10, N = 16), MCG_lowSMA = 2.31 (SDCG_lowSMA = 1.10, N = 16).

Life and Work Satisfaction

Life satisfaction, a core dimension of subjective well-being [33], was measured by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) [50]. All items were assessed using Likert scales (1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”). The data of SWLS showed good reliability (all Cronbach’s αs > 0.86).

This study measured participants’ work satisfaction using the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) [51], to determine whether short-term abstinence has a positive effect on people’s working experience (from 1-very dissatisfied to 5-very satisfied). The data of MSQ also showed good reliability (all Cronbach’s αs > 0.87).

Daily Evaluation

The daily evaluation of life and work was measured by two single questions. They were “From 1 to 10, how much would you evaluate your today’s life?” and “From 1 to 10, how much would you evaluate your today’s work?” (1 = “very bad”, 10 = “very good”).

Data Collection and Analysis

Diary and Subjective Measures

Daily diary and the subjective measures were distributed to users as online questionnaires. Data were collected and saved in an online system. Researchers would remind participants who might have forgotten it after a daily check.

We conducted statistical analyses using R. Repeated measure analyses of variance (ANOVAs; within-between factor-design) were calculated to test possible effects of short-term abstinence on life and work satisfaction and to compare the two research groups (EG and CG). For all measures, Mauchly’s tests indicated that the assumption of sphericity was met. Generalized eta-squared (η2g) served as the effect-size measure of main effects and interaction effects [52]. Cohen’s d was applied as effect-size measure of post-hoc comparisons between groups [53].

Follow-Up Survey

Two weeks after the experiment, participants in the EG took a follow-up survey about their cognitions and behaviors after the experiment. The data from the two addiction groups were contrasted by Pearson’s Chi-squared tests. Considering the small sample size, Yates’ continuity correction was applied [54].

Qualitative Analysis

Content analysis was used to interpret the qualitative data. Four independent volunteers helped code the manuscripts. First, they analyzed all the diaries and interview manuscripts of five participants, based on which they developed their own initial coding books focusing on the three core topics in the CBT framework (see Fig. 1): compensatory behaviors, feelings, and thoughts. Then, the four coders had a discussion and formed a revised codebook. According to the unified codebook, all qualitative data were analyzed with every manuscript coded by a different pair of volunteers. Kappa agreement scores were calculated to determine whether the two pairs of coders arrived at an agreement on the same manuscript [55, 56].

Results

Effects of Short-Term Abstinence

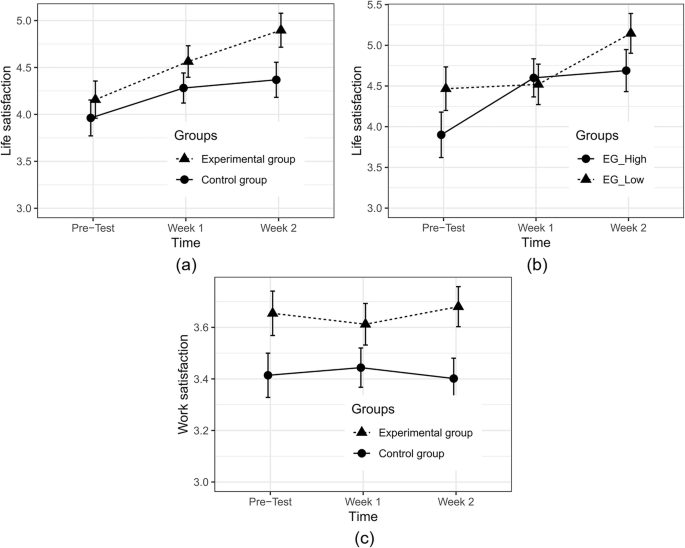

The descriptive data of life and work satisfaction measured at different time points are shown in Table 2. Figure 3 visualizes the changes of life and work satisfaction.

Life Satisfaction

For life satisfaction, the result of ANOVA showed that the main effect of time was significant (F(2,126) = 18.25, p < 0.001, η2g = 0.051). Life satisfaction of participants in both groups increased with the experiment. The difference between the pre-test and the post-test showed an interaction effect (F(1,63) = 18.25, p < 0.08, η2g = 0.006). The pairwise comparisons indicated that, at the baseline, no significant difference existed between groups. After the experiment, however, participants in the EG reported higher life satisfaction than the participants in the CG (see Fig. 3a and Table 2). This finding suggested that, besides the effects of self-monitoring, short-term abstinence had positive effects on users’ life satisfaction.

We further examined the effects of SMA on the change of life satisfaction in both groups. ANOVA of the EG data revealed a significant interaction effect of SMA and time (F(2,62) = 3.14, p = 0.05, η2g = 0.018). Life satisfaction of participants with high SMA mainly increased in the first week, while life satisfaction of participants with low SMA mainly increased in the second week (see Fig. 3b), implying that users with higher SMA might respond quicker to the CBT-based short-term abstinence intervention than users with lower SMA. ANOVA of the CG data indicated no significant influence of SMA.

The effects of abstinence conditions (i.e. abstinence during work hours, during off hours, or no abstinence) on user self-reported daily evaluation of life were examined. We found no significant difference among abstinence conditions.

Work Satisfaction

For work satisfaction, the result of ANOVA showed no significant main effect of time (F(1,63) = 0.05, p = 0.94, η2g = 0.000) and no significant interaction effect (F(2,126) = 1.02, p = 0.36, η2g = 0.002). Users’ overall work satisfaction did not increase during the two weeks’ intervention (see Fig. 3c).

The main effect of abstinence condition was significant on daily evaluation of work (F(2, 64) = 3.14, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.021). Participants reported higher daily work satisfaction when they abstained from social media during work hours (Mwork = 7.00, SDwork = 1.37) than during off hours (Moff = 6.50, SDoff = 1.59) or taking no abstinence (Mno_abstinence = 6.60, SDno_abstinence = 1.50).

Behaviors, Feelings and Thoughts

Qualitative data were analysed according to the framework shown in Fig. 1. The kappa scores showed perfect agreement (Kbehaviors = 0.91, Kfeelings = 0.87, Kthoughts = 0.86). Table 3 summarizes participants’ compensatory behaviors during abstinence. Table 4 summarizes feelings of abstinence. Table 5 summarizes corresponding thoughts. The Tables 3, 4, 5 provide an example quote for each item, followed by the numbers and percentages of participants who mentioned this item.

We categorized participants’ behaviors during abstinence into three groups: active behaviors, passive behaviors, and abstinence efforts (Table 3). These behaviors may lead to participants’ positive and negative feelings of abstinence (Table 4), and these feelings could reconstruct or strengthen their thoughts. Participants’ thoughts were classified as self-reflections of their own behaviors and cognitions of social media (Table 5). We used qualitative analysis to reveal possible associations among users’ behaviors, feelings and thoughts resulting from the short-term abstinence. The results of the qualitative analyses indicated that the intervention could have both positive and negative influences.

Positive Influences

On the positive side, participants conducted active behaviors to compensate the non-use of social media in two ways. In one way, short-term abstinence motivated participants to conduct an activity they would possibly not do in a routine life, such as picking up an old hobby, doing exercises, making daily plans and summaries, and conducting off-line social activities. For example, a participant (female, 36, teacher) told us:

“Usually when I come home, I am busy doing housework or browsing social media to kill time. In the abstinence, one day, I could not use social media, so I sat beside my son, watching him doing homework. I suddenly noticed I did not look directly into his eyes for a few days. I was shocked and decided to talk with him more. Well, the relationship between me and my son is closer anyway, and I wish to encourage my husband to do it too”.

In the other way, participants take abstinence to avoid possible distractions during a planned activity, including working, studying, and appointed off-line interaction activities. For example, a participant stated that abstinence improved the quality of her dinner communication with an old friend, because they kept talking in deep and never checked phones:

“I conducted abstinence during an appointed dinner with a friend, and we agreed not to watch mobile phones during dinner. It felt so good. We ate a mung bean soup for three hours and had a lot to talk about. This was different from the case when we texted via social media. It’s really fun to keep talking with friends and not check social media.” (Female, 29, Interaction Designer)

Participants reported they had positive feelings when conducting active behaviors during abstinence (Table 4). For example, with less distractions from social media, participants could concentrate on one task for a rather long time, and they felt the time integrity and high autonomy. A participant told us, he enjoyed the free time from social media distractions in doing what he like:

“I can do things I want during abstinence in off hours. For example, I went out for a walk, played tennis, and watched movies. I feel like I have more free time. People should have their own time and do things they like. In the last two weeks, I have done more things I want than before. Just feel I am in control of myself other than be controlled by social media.” (Male, 28, Research Assistant)

In other examples, participants said abstinence made them finish tasks more efficiently, and they felt higher productivity:

“Abstinence could really improve my productivity. At least it could improve efficiency. For some of my work, I felt abstinence quite necessary. The abstinence will let you concentrate more on the task, and thus, your productivity improved. In the future, if I want to finish some work quickly, I will take abstinence.” (Male, 27, Investment Manager)

The high productivity during work have positive influence on feelings. The good feelings resulting from task accomplishment have influences on both work and life. A participant reported:

“During abstinence in work hours, I have high productivity, and I ever finished the whole day’s work in a half day. After finishing all the tasks, I was really in a good mood. The good mood lasted even when I came home from work.” (Female, 27, Safety Inspector)

The self-fulfillment of completing tasks, and the enjoyment of taking exercises and hobbies, the improved off-line social interactions all triggered positive feelings. Positive feelings resulting from abstinence motivated participants’ self-reflections on the contrast between the experience of abstinence and routine lives, which may reconstruct or strengthen their cognitions. We concluded the main reflections reported by participants about their self-behaviors in Table 5, among which, the waste of time on social media (66.7%) and the dependency for social media (51.5%) were the most mentioned reflections. More participants with high SMA (72.2%) reported dependency for social media than participants with low SMA (26.7%). Some participants also introspected the time fragment caused by social media:

“Before abstinence, I think social media is a great way to kill the fragmented time. People can use it to relieve the short but painful boredom of waiting for the elevator or taking the subway. But I just found, actually, it was social media that fragmented our time into small pieces, and we have to fill in the pieces by aimlessly pulling-down the updates.” (Male, 29, Trader)

Negative Influences

On the negative side, nearly half (45.5%) of the participants reported they ever had passive behaviors during abstinence. A typical passive behavior is spending time aimlessly. The interview results showed that, in order to complete the required abstinence, most participants had to take great efforts, especially in the early stage of the two-week intervention session. 72.7% of the participants reported they used external forces to get away from social media, such as locking the phone in the drawers or turning it off. This situation was more commonly reported by participants with high SMA (88.9%) than participants with low SMA (53.3%). Similarly, more than half (54.5%) of the participants mentioned that they had to keep strengthening the belief of abstinence in order to finish it.

Corresponding to the passive behaviors and abstinence efforts, most participants ever had negative feelings at the early stage of the intervention session. The most commonly reported negative feeling was the FoMO (90.9%), whereas, the qualitative results revealed that the FoMO was relieved as the intervention session continued. More than half of the participants (60.6%) reported that the FoMO was alleviated when they repeatedly found nothing important was missed during abstinence:

“In the beginning, I felt worried (during abstinence) that people would be looking for me. But now I don’t worry anymore because I found I didn’t miss any useful information. What I have received are some unimportant messages in the chat groups, or some advertisement, or some messages that could be answered at any time. Anyway, none of them are particularly urgent. The sense of anxiety is weakening.” (Female, 25, Research Assistant)

Similarly, even though 33.3% of participants thought the abstinence was hard to conduct in the early stage, their self-efficacy improved as they successfully finished abstinence for a few times (see Table 4 – positive feelings). Another commonly mentioned (81.8%) negative feeling is the perceived inconvenience. As so many different affordances were embedded in social media and they were used in various contexts, even though the abstinence only took 2.5 h, the inconvenience was still a problem. For example, a participant told us the inconvenience he faced when not using WeChat:

“I can’t do without WeChat. Sometimes I use WeChat to communicate at work, and I also need it during non-working hours. For example, when I take a taxi or buy something, without Wechat, I can’t pay. You don’t just use it to kill time. It’s really necessary for life.” (Male, 26, Civil Servant)

Perceived inconvenience had driven participants to consider the true values of social media. The values for online social interaction and information exchange were affirmed. 48.5% of the participant thought using social media was a basic need in their lives. Differently, a few (15.2%) participants found social media was not as important as they assumed before the intervention. We think participants’ affirmation of the values in social media does not contradict the idea of short-term abstinence. However, understanding the true values of social media may lead users to use it more actively and rationally. We will talk more about this issue in the discussion part.

Post-Intervention Behaviors

To further explore the influence of short-term abstinence on participants, we conducted a follow-up survey. We found a difference between groups with various SMA. Thirteen of the 18 participants with high SMA reported that they ever had an intention of abstinence (72.2%). The number was only four (26.7%) for the participants with low SMA. The results of Pearson’s Chi-squared test with Yates’ continuity correction indicated significant difference (χ2(1) = 5.10, p < 0.05, odds ratio = 7.15). We also investigated the participants’ exact abstinence behaviors. Eight of the 18 participants with high SMA admitted that they had actively abstained from social media after the experiment (44.4%). Only 3 participants with low SMA had this behavior (20.0%, χ2(1) = 1.24, p = 0.27, odds ratio = 3.2).

Discussion

This study proposed a CBT-based short-term abstinence intervention to treat problematic social media use. We conducted a mixed method study to examine the effects of this intervention strategy and to reveal the underlying mechanisms.

The first research question is regarding the efficacy of the intervention strategy. The quantitative results of our study proved the positive influence of the CBT-based short-term abstinence intervention on users’ life satisfaction. In addition to interventions that require users to get way from social media continuously over one week [32, 33], our intervention strategy protects users’ basic need for daily social media use and may have higher feasibility. It allows users to develop a rational usage habit rather than quit social media.

Our intervention included diaries to help users record their behaviors, feelings, and thoughts. The quantitative results of our study suggested that even though self-monitoring alone could have positive influences on users’ life satisfaction (the CG), the combination of short-term abstinence and self-monitoring had significantly stronger effects (the EG). This finding supported the positive effects of short-term abstinence. We must admit self-monitoring (like taking diaries) is a commonly used tool in CBT and is an essential part of our intervention strategy. But what if users do not want to conduct self-monitoring in real practice? So an interesting question is how will short-term abstinence alone influence users’ well-being. This question is worthwhile to be explored in future research.

Regarding work satisfaction, the results of our study indicated no significant influence of the intervention on work satisfaction measured by the MSQ [51]. We think a possible reason may be that the scale includes many detailed descriptions of work conditions (like the supervision-human relations and the compensation), which are not inclined to be influenced by the users’ abstinence behaviors in two weeks. However, we found the abstinence during work hours will positively influence users’ daily evaluation for the day’s work. Qualitative results of the diaries and interviews suggest the improved daily evaluation for work may result from less distractions during abstinence. Participants perceived higher autonomy of time and their work. The productivity improved, and participants felt fulfilment after finishing work efficiently.

Consistent with former studies [21, 33], our findings suggested that the effects of the intervention varied among users with different SMA. More participants with high SMA thought abstaining from social media was difficult and more of them took external forces to finish the required abstinence (like turning off the phone or locking the phone in the drawers). The improvement of life satisfaction of participants with high SMA also happened earlier than that of participants with low SMA. All these findings suggest the intervention may have a quicker and stronger effect on participants with high SMA. When considering this finding, we have to take care that the measures of SMA in our study was based on users’ self-reported scores, and so are most psychological scales used to measure SMA. The different effects of intervention between addiction groups may partially relate to users’ self-awareness.

The second research question is regarding the underlying cognitive and behavioral mechanisms of how abstinence influences users. From the qualitative analyses, we summarized users’ behaviors, feelings, and cognitions resulting from the abstinence, and we revealed the potential associations. In line with the previous study on abstinence [21], the results of our study suggests that the CBT-based short-term abstinence causes both positive and negative influences. On the positive side, the results revealed that disengagement from social media protects users from disturbing and allows them to focus on other meaningful things. Participants, therefore, had positive feelings like increased autonomy, improved productivity, perceived fulfilment, and closer off-line relationship. According to the reward-based learning process [27], the positive feelings resulting from the compensatory behaviors could be rewarding for users, thus, they may conduct these behaviors to displace the use of social media in future. The positive feelings also motivated participants to reflect on their social media use and make behavioral changes. One the negative side, FoMO, inconvenience, and difficulty of breaking a habit are main problems of social media abstinence. However, as the abstinence went on, the negative impact decreased. The results of our study indicated that FoMO and perceived difficulty were alleviated, as participants got used to the abstinence. The perceived inconvenience motivated participants to think about what are the key values of social media to them. Understanding the values of social media, they may use it more actively. Previous studies found that passive behaviors were highly related to unpleasant emotions, but active use will not necessarily cause negative effects [30, 33]. Thus, even though perceived inconvenience is a negative feeling during abstinence, it may still benefit users as if it could guide them to actively use social media.

Our findings suggested that users’ self-awareness of their social media use will influence the intention to take abstinence after experiment. For example, a participant (28, male, SMA = 1) told us he did not think he had problematic social media use, and he thought taking abstinence was not necessary for him. This is a possible reason why the effects of the intervention varied with self-reported SMA. Thus, when implementing the abstinence intervention, the SMA and potential participants’ self-awareness should be considered.

Limitations and Research Directions

Several limitations are noteworthy. First, in order to contrast the influence of abstinence during work hours and off hours, this study measured participants’ overall life satisfaction and work satisfaction, which might miss more detailed information on why the satisfaction was influenced. As suggested in the qualitative results, increased autonomy, improved productivity, closer off-line relationship and relieved FoMO were main benefits of short-term abstinence. Future studies may directly measure these constructs besides satisfaction, which may give a more detailed description of the effects of the intervention. Second, although no significant gender difference exited between the EG and the CG, there was a gender bias in the EG, and the sample size of our study is not large. Future studies may verify the efficacy of the CBT-based short-term abstinence with a larger and more gender balanced sample. Third, despite the significant results, we are not sure the intervention strategy in our study (2.5 h/time, 4 times/week, 2 weeks) is most effective. Future studies may investigate different length of abstinence (more or less than 2.5 h), different times in a week, and different length of the intervention session (longer than 2 weeks) to determine the best intervention settings. Forth, as we mentioned above, taking diaries is an essential part of the intervention in our study to increase self-awareness. Considering some users may be unwilling to take a dairy in practice, it will be an interesting topic to examine the effects of short-term abstinence alone without diaries in future research.

Conclusion

Our study proposed a CBT-based short-term abstinence intervention to treat problematic social media use. In order to improve the feasibility of abstinence, this intervention only requires users to get away from social media for a few hours (2.5 h in this study) a time. We conducted a mixed method study to examine the effectiveness of this intervention, and to reveal the underlying mechanisms of how the intervention influences users. Our findings demonstrate that the intervention improves users’ overall life satisfaction, and intervention during work hours improves users’ daily evaluation for their work. The results also revealed that users with high self-reported SMA are more susceptible to the intervention. According to CBT, the qualitative results of diaries and interviews unveiled associations among users’ behaviors, feelings, and cognitions during and after abstinence, revealing that the intervention mainly benefits users from improved productivity, increased autonomy, closer off-line relationship, and alleviated FoMO. Together, these findings indicate that CBT-based short-term abstinence is a promising intervention to deal with problematic social media use.

References

1.

Andreassen CS. Online Social network site addiction: a comprehensive review. Curr Addict Rep. 2015;2:175–84.

2.

Yi LL, Sidani JE, Shensa A, Radovic A, Miller E, Colditz JB, et al. Association between social media use and depression among US young adults. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:323–31.

3.

Pontes HM, Taylor M, Stavropoulos V. Beyond “Facebook addiction”: the role of cognitive-related factors and psychiatric distress in social networking site addiction. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2018;21:240–7.

4.

Shensa A, Escobar-Viera CG, Sidani JE, Bowman ND, Marshal MP, Primack BA. Problematic social media use and depressive symptoms among U.S. young adults: a nationally-representative study. Soc Sci Med. 2017;182:150–7.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

5.

Worsley JD, Mansfield R, Corcoran R. Attachment anxiety and problematic Social media use: the mediating role of well-being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2018;21:563–8.

6.

Hawk ST, van den Eijnden RJ, van Lissa CJ, ter Bogt TF. Narcissistic adolescents’ attention-seeking following social rejection: links with social media disclosure, problematic social media use, and smartphone stress. Comput Hum Behav. 2019;92:65–75.

7.

Kross E, Verduyn P, Demiralp E, Park J, Lee DS, Lin N, et al. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69841.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

8.

van Rooij A, Ferguson C, van de Mheen D, Schoenmakers T. Time to abandon internet addiction? Predicting problematic internet, game, and social media use from psychosocial well-being and application use. Clin Neuropsychiatry J Treat Eval. 2017;14:113–21.

9.

van Zoonen W, Verhoeven JWM, Vliegenthart R. Understanding the consequences of public social media use for work. Eur Manag J. 2017;35:595–605.

10.

Turel O, Qahri-Saremi H. Problematic use of social networking sites: antecedents and consequence from a dual-system theory perspective. J Manag Inf Syst. 2016;33:1087–116.

11.

Hawi NS, Samaha M. The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university students. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2017;35:576–86.

12.

Baumer EPS, Adams P, Khovanskaya VD, Liao TC, Smith ME, Sosik VS, et al. Limiting, leaving, and (re)lapsing: an exploration of Facebook non-use practices and experiences. 2013;10.

13.

Charoensukmongkol P. Effects of support and job demands on social media use and work outcomes. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;36:340–9.

14.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Online social networking and addiction—a review of the psychological literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:3528–52.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

15.

Müller KW, Dreier M, Beutel ME, Duven E, Giralt S, Wölfling K. A hidden type of internet addiction? Intense and addictive use of social networking sites in adolescents. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;55:172–7.

16.

Ryan T, Chester A, Reece J, Xenos S. The uses and abuses of Facebook: a review of Facebook addiction. J Behav Addict. 2014;3:133–48.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

17.

Pantic I. Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17:652–7.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

18.

van den Eijnden RJJM, Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM. The Social media disorder scale. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;61:478–87.

19.

Stieger S, Lewetz D. A week without using social media: results from an ecological momentary intervention study using smartphones. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2018;21:618–24.

20.

Turel O, Brevers D, Bechara A. Time distortion when users at-risk for social media addiction engage in non-social media tasks. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;97:84–8.

21.

Turel O, Cavagnaro DR, Meshi D. Short abstinence from online social networking sites reduces perceived stress, especially in excessive users. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:947–53.

22.

Blackwell D, Leaman C, Tramposch R, Osborne C, Liss M. Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Personal Individ Differ. 2017;116:69–72.

23.

Fang J, Wang X, Wen Z, Zhou J. Fear of missing out and problematic social media use as mediators between emotional support from social media and phubbing behavior. Addict Behav. 2020;107:106430.

24.

Holte AJ, Ferraro FR. Anxious, bored, and (maybe) missing out: evaluation of anxiety attachment, boredom proneness, and fear of missing out (FoMO). Comput Hum Behav. 2020;112:106465.

25.

Casale S, Rugai L, Fioravanti G. Exploring the role of positive metacognitions in explaining the association between the fear of missing out and social media addiction. Addict Behav. 2018;85:83–7.

26.

Fabris MA, Marengo D, Longobardi C, Settanni M. Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: the role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media. Addict Behav. 2020;106:106364.

27.

Brewer J. Mindfulness training for addictions: has neuroscience revealed a brain hack by which awareness subverts the addictive process? Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;28:198–203.

28.

Hofmann W, Van Dillen L. Desire: the new hot spot in self-control research. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2012;21:317–22.

29.

Grant JE, Potenza MN, Weinstein A, Gorelick DA. Introduction to behavioral addictions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:233–41.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

30.

Hall JA, Johnson RM, Ross EM. Where does the time go? An experimental test of what social media displaces and displaced activities’ associations with affective well-being and quality of day. New Media Soc. 2018;1461444818804775.

31.

Jorge A. Social media, interrupted: users recounting temporary disconnection on instagram. Soc Media Soc. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2019;5:2056305119881691.

32.

Schoenebeck SY. Giving up Twitter for Lent: how and why we take breaks from social media. ACM Press; 2014 [cited 2018 Jun 20]. p. 773–82. Available from: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2556288.2556983

33.

Tromholt M. The Facebook experiment: quitting Facebook leads to higher levels of well-being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2016;19:661–6.

34.

Brailovskaia J, Ströse F, Schillack H, Margraf J. Less Facebook use – more well-being and a healthier lifestyle? An experimental intervention study. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;108:106332.

35.

Andreassen CS, Pallesen S, Griffiths MD. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. Addict Behav. 2017;64:287–93.

36.

Błachnio A, Przepiorka A, Pantic I. Association between Facebook addiction, self-esteem and life satisfaction: a cross-sectional study. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;55:701–5.

37.

Hormes JM, Kearns B, Timko CA. Craving Facebook? Behavioral addiction to online social networking and its association with emotion regulation deficits. Addiction. 2014;109:2079–88.

38.

Wang C, Lee MKO, Hua Z. A theory of social media dependence: evidence from microblog users. Decis Support Syst. 2015;69:40–9.

39.

Davis RA. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological internet use. Comput Hum Behav. 2001;17:187–95.

40.

Caplan SE. Theory and measurement of generalized problematic internet use: a two-step approach. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26:1089–97.

41.

Mai Y, Hu J, Yan Z, Zhen S, Wang S, Zhang W. Structure and function of maladaptive cognitions in pathological internet use among Chinese adolescents. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28:2376–86.

42.

Breckler SJ. Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984;47:1191–205.

43.

Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:17–31.

44.

Young KS. Cognitive behavior therapy with internet addicts: treatment outcomes and implications. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007;10:671–9.

45.

Young KS. CBT-IA: the first treatment model for internet addiction. J Cogn Psychother. 2011;25:304–12.

46.

Korotitsch WJ, Nelson-Gray RO. An overview of self-monitoring research in assessment and treatment. Psychol Assess. American Psychological Association; 1999;11:415.

47.

Kim SM, Han DH, Lee YS, Renshaw PF. Combined cognitive behavioral therapy and bupropion for the treatment of problematic on-line game play in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28:1954–9.

48.

Young KS. Internet addiction: symptoms, evaluation and treatment. 1999;

49.

Zhou SX, Leung L. Gratification, loneliness, leisure boredom, and self-esteem as predictors of SNS-game addiction and usage pattern among Chinese college students. Int J Cyber Behav Psychol Learn. IGI Global; 2012.

50.

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:71–5.

51.

Weiss DJ, Dawis RV, England GW. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minn Stud Vocat Rehabil. 1967.

52.

Bakeman R. Recommended effect size statistics for repeated measures designs. Behav Res Methods. 2005;37:379–84.

53.

Sawilowsky SS. New effect size rules of thumb. J Mod Appl Stat Methods. 2009;8:597–9.

54.

Howell DC. Statistical methods for psychology: Cengage Learning; 2009.

55.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

56.

Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37:360–3.